Jean Denton’s own story of her drive to Sydney

Duckhams report

It seems incredible on reflection,that not only has the London-Sydney Marathon come and gone, but that I have in fact been all the way to Australia and back, It is very difficult to recall the events of that month, they all happened so quickly and even the ones I recall have a vaguely unreal quality about them.

What stands out without a doubt is the four solid months before we left when our whole lives were given over to building up the MGB for the epic, and raising the money to pay for the trip – so much so that we now wonder what else we used to do in our spare time.

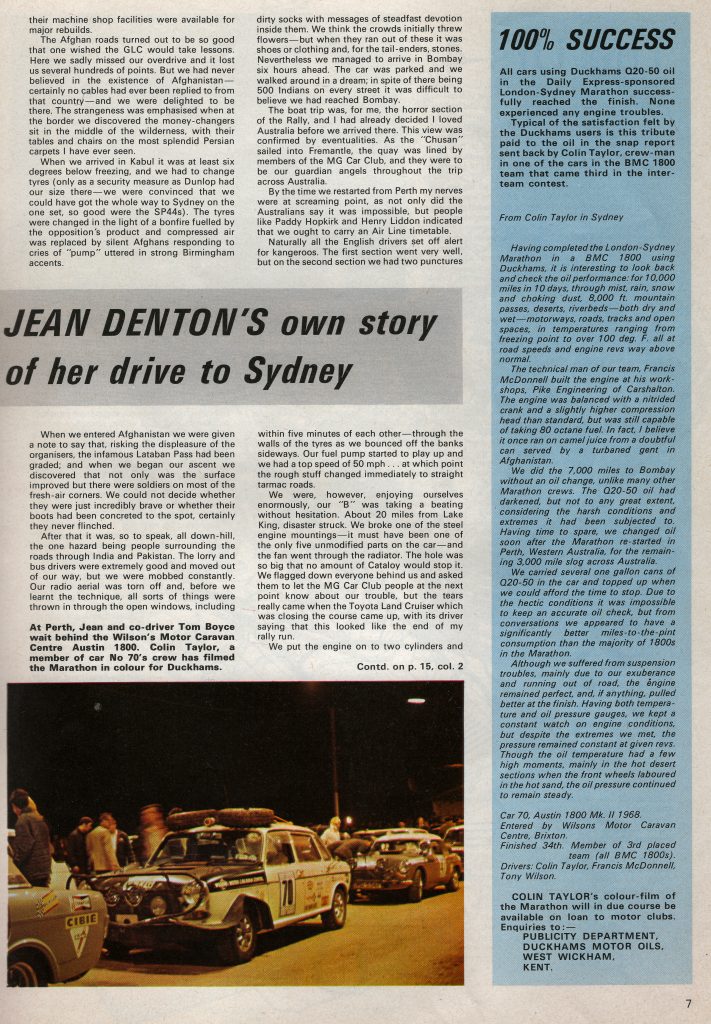

We used the MGB I had raced in Europe during the summer and stripped it down to a body shell again and the engine down to the block, We double – welded all the seams which seemed likely to be heavily stressed on the journey, and brought the fuel and brake lines inside the car in order to protect them.

We already had a double tank fitted and to cope with the car’s additional fuel requirements we built a rack to carry three five-gallon jerrycans. Working on the principle that the drag of the car should be kept as low as possible – already being at an advantage here with the MGB – we steadfastly refused to carry any equipment on the roof. One spare wheel went inside the boot and the other was carried outside the boot lid. To cope with the extra weight at the back of the car, special springs and extra dampers were fitted. Fortunately BMC had developed springs for those police forces who carry radio equipment in the boot of their MGs.

We had extra long coil springs made up for the front of the car and the result was that unladen the lowest point on the “B” was still 7 1/2″ off the ground. This rather threw those critics who said the MG was too low for such an event. One of the most frequent questions in Sydney “what number exhaust system we were on” and we were delighted to be able to stress that the very same one that left Crystal Palace arrived at Warwick Farm.

Rumours were flying around about the dangers of kangaroos on the Australian section and Rearsby Automotive made up an absolutely splendid ‘roo guard for us. In fact it was so fearsome that it terrified all the kangaroos on sight and I had to go to one of Sydney’s National Parks in order to get my first close look at one.

It seems that the Porsche team appeared with a very tiny guard initially as they went round to London Zoo to view the opposition and mistook the wallabies for kangaroos. Upon being told that the kangaroos came in sizes up to six foot, the final all-enclosing guard was built.

Cibié very kindly gave lights to all private entrants and we ran with extra powerful headlamps, two spots and two fogs, plus a reversing light. Apparently Fords rejected an offer latter, but neither Tom nor myself had such faith in our navigation. These additions

changed the appearance of the outside of the car. Inside, the major modification and the one to arouse most comment, both polite and dubious, was the substitution of a bed for the passenger seat. This was designed by ourselves. It consisted of an alloy tube frame with webbing stretched across and foam on top. We had decided that with only two of us in the car we had to make sure that we slept soundly during rest periods. In fact apart from Australia when the going was rough one rattled about too much, we slept like logs, and the driver would have to start waking the passenger at least half-an-hour before it was time to change. Under the bed and in the remainder of the space in the boot we packed as many spares as possible to make ourselves independent. In retrospect, we overdid it. We carried spare clutches, brakes, front and rear springs, stub axles, filters, pistons, snow chains, etc.

People were very generous in helping towards our participation. The magazine NOVA took over the entry and provided us with suitable clothing for the trip, along with various other goodies — for instance a cordless shaver for co-driver Tom — cleansing pads for both of us, radio and tape recorder from Phillips, and a medical kit to which my doctor added morphine and syringes.

I was also given an especially large handbag which in the event proved a great advantage for, having spent several years learning that a girl never leaves her handbag behind, we were constantly in possesion of our documents whereas some of the men decided to leave theirs in the oddest places. The only problem on this score arose when we had to sleep in beds put up on a landing in a hotel in Kabul when, to protect my precious carnet along with hundreds of Monopoly – type bank notes, I had to take this enormous handbag to bed with me,

Duckhams assisted the venture. And BP provided me with fuel along the route — sometimes with glee, out of the Castrol tanker. Gibeys of Australia christened the car “Miss Smirnoff” and were kind enough to provide constant reminders of our heritage, especially welcome by the time we reached Sydney. Air India provided us with tickets home from wherever we ground to a halt — which, of course, made us determined to extract maximum value by reaching Sydney, Indeed we set off with extra determination just because everyone said it could not be done by two amateurs in an MGB — that was just the sort of incentive we needed!

And we certainly could do with some sort of encouragement by the time we got to Paris on the first day as by then we had lost our overdrive,starter motor and windscreen wipers. The first we never found again, which upset our petrol calculations and top speed enormously. The starter motor came and went with the guarantee of always disappearing when there was no slope on which to park the car. Fortunately even Tom recognised that it was easier for me to be inside than for me to push with his 14 stone filling the driver’s seat.

The trip through France was fairly uneventful apart from the confusion caused by the French police issuing an alternative route which ignored the autoroutes we had all planned to use. Much to our amazement the Australians obeyed the police instructions to a man — and it was only later, when we encoutered the Australian police, that we understood their respect for authority.

Over the Alps we discovered our team’s secret weapon. As soon as we encountered this mountain range, as with any other along the route, I was car sick. This was not only unpleasant for me but equally so for poor Tom, having to ignore the odd noises and moans. However, we quickly learnt that if I wound down a window and stuck my head out, the car behind backed off — and really all this unfortunate illness cost me was enjoyment of the scenery. The Army team did offer to come to my rescue on this matter, but we discovered the pills they were so keen I should take were only prescribed for cattle.

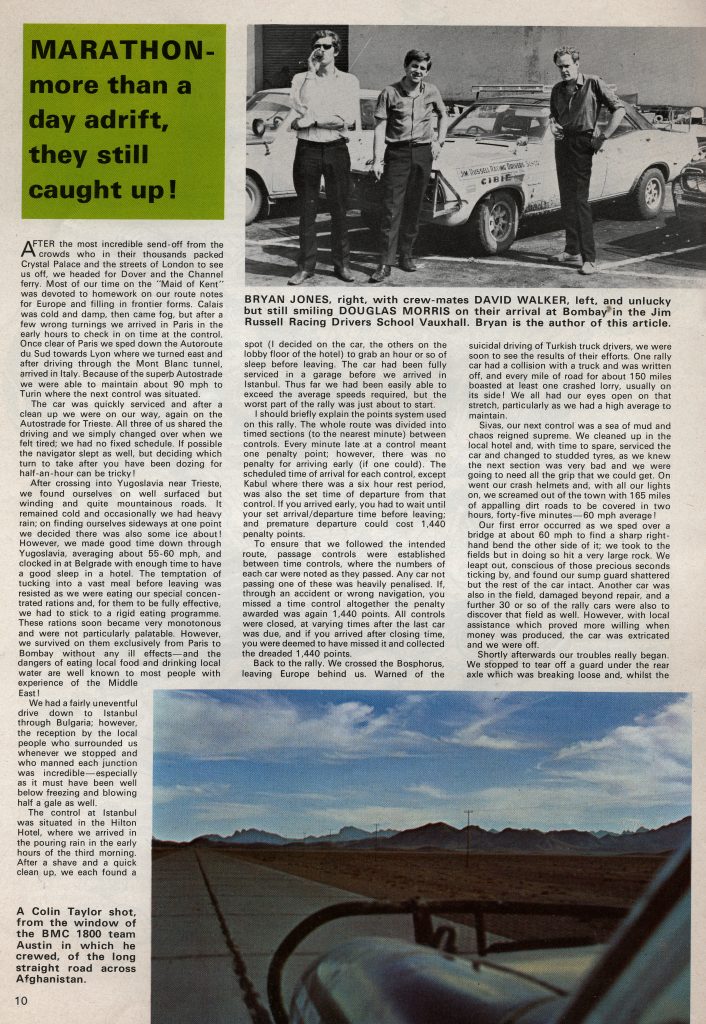

Everyone arrived in Turin early and set off for Belgrade where again most of us arrived with time to go to bed. This also occured in Istanbul although by then the weather was beginning to be less favourable. It poured continuously all the way through Bulgaria and Turkey, withoutdampening in the slightest the tremendous enthusiasm of the Bulgarian people. In Istanbul I had not booked a room, but Peter Browning of British Leyland very kindly let me use a spare bed in one of his teams’ rooms. This did not worry the driver using the other bed but it certainly amusedhis co-drivers when they arrived to collect him for departure.

We all felt the Marathon began after Istanbul. Up to there we had been on surfaced roads and certainly all of us felt that we shouldbe able to get in a car and drive as far as Istanbul for our summer holiday if we wanted. However, it was just afterwe left the ferry that we passed one of the first accidents of the Marathon. This turned out to be Peter Lumsden’s car and as Peter had very kindly let us build our Marathon car in his garage, our hearts went out to him.

Our Journey to Sivas was uneventful and we set about doing a routine service before we departed into the mountains. This was complicated by the collapse of the jack, fortunatley without damage to the car, and eventually we departed to do the first of the special stages.

We were aiming to get to Sydney, so we took this one very cautiously and in the end had a Porsche for company, using our lights to replace their own. Not far doen this stage we came accross one of the privately entered 1800s hanging off a bridge, but fortunately there were about fifty Turks around, defeating the law of gravity.

The most noteworthy part of the next 1,000 miles was the efficiency of the Tehran control. We had met the members of the Iran Motor Club whilst competing in the Lebanon last year, and they gave us a tremendous welcome. For the first time Tom had someone to help him do the servicing, and we had the chance to have a shower and, had we not felt so sociable, there were dormitories available for sleep. The control was located in Phillips factory and the whole of their machine shop facilities were available for major rebuilds.

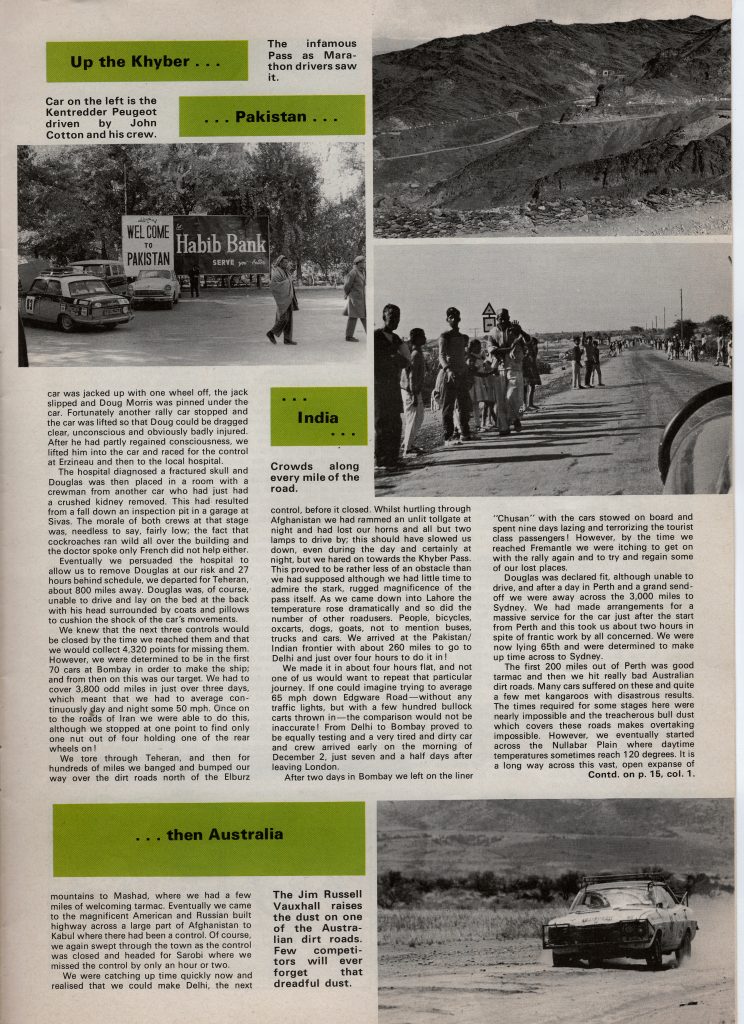

the Afghan roads turned out to be so good that one wished the GLC would take lessons. Here we sadly missed our overdrive and it lost us several hundred points. But we had never believed in the existence of Afghanistan — certainly no cables had ever been replied from that country — and we were delighted to be there. The strangeness was emphasised when at the border we discovered the money-changers sit in the middle of the wilderness, with their tables and chairs on the most splendid Persian carpets I have ever seen.

we arrived in Kabul it was at least six degrees below freezing, and we had to change tyres (only as security measure as Dunlop had our size there — we were convinced that we could have gone all the way to Sydney on the one set, so good were the SP44s). the tyres were changed in the light of a bonfire fuelled by the opposition’s product and compressed air was replaced by silent Afghans responding to cries of “pump” uttered in strong Birmingham accents.

When we entered Afghanistan we were given a note to say that, risking the displeasure of the organisers, the infamous Lataban Pass had been graded; and when we began our ascent we discovered that not only was the surface improved but there were soldiers on most of the fresh – air corners. We could not decide whether they were just incredibly brave or whether their boots had been concreted to the spot, certainly they never flinched.

After that it was, so to speak, all down – hill, the one hazard being people surrounding the roads through India and Pakistan. The lorry and bus drivers were extremley good and moved out of our way, but we were mobbed constantly. Our radio aerial was torn off and, before we learnt the technique, all sorts of things were thrown in through the open windows, including dirty socks with messages of steadfast devotion inside them. We think the crowds initially threw flowers — but when they ran out of these it was shoes or clothing and, for the tail-enders, stones. Nevertheless we managed to arrive in Bombay six hours ahead. The car was parked and we walked around in a dream; in spite of there being 500 indians on every street it was difficult to believe we had reached Bombay.

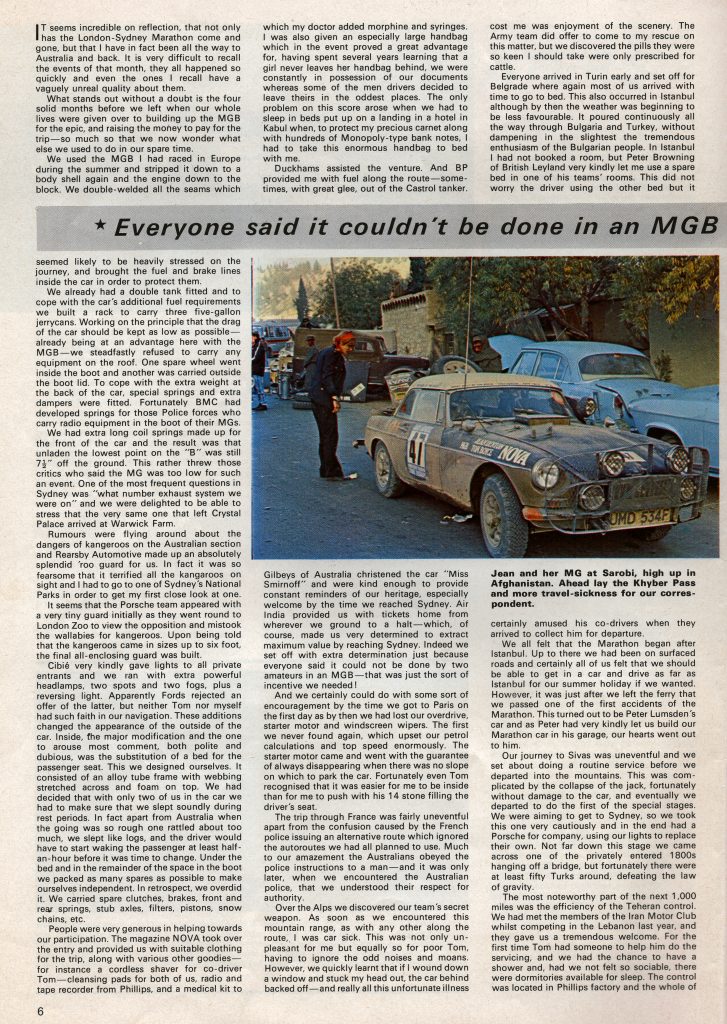

The boat trip was, for me, the horror section of the Rally, and I had already decided I loved Australia before we arrived there. This view was confirmed by eventualities. As the “Chusan” sailed into Fremantle, the quay was lined by members of the MG Car Club, and they were to be our guardian angels throughout the trip across Australia.

By the time we restarted from Perth my nerves were at screaming point, as not only did the Australians say it was impossible, but people like Paddy Hopkirk and henry Liddon indicated that we ought to carry an Air Line timetable.

Naturally all the english drivers set off alert for kangaroos. The first section went very well, but on the second section we had two punctures within five minutes of each other — through the walls of the tyres as we bounced off the banks sideways. Our fuel pump started to play up and we had a top speed of 50 mph … at which point the rough stuff changed immediately to straight tarmac roads.

We were, however, enjoying ourselves enormously, our “B” was taking a beating without hesitation. About 20 miles from Lake King, disaster struck. We broke one of the steel engine mountings — it must have been one of the only five unmodified parts on the car — and the fan went through the radiator. The hole was so big no amount of Cataloy would stop it. We flagged down everyone behind us and asked them to let the MG Car Club people at the next point know about our trouble, but the tears came when the Toyota Land Cruiser which was closing the course came up, with its driver saying that this looked like the end of my rally run.

We put the engine on to two cylinders and tried to run on the heater. But as it was midday and we were on the edge of the desert we could only do five miles at a time this way. When the boys eventually did bring a radiator back to us, we both thought the car appearing on the horizon was a mirage.

However, we got the MG going again and,although officially we were out of time at that stage, we set off to cross the Nullabar and hoped to pull back the rally. In the end, by averaging 85 mph for six hours, we arrived at Ceduna with twenty minutes to spare. After that it was a case of pressing on as quickly as possible to try to make up time to weld the engine mounting — which we did, losing another hour.

The only other complication to our life was the failure of the speedometer which kept functioning at half speed, so that T-junctions would come up four miles early and be taken flat out. Eventually it packed up altogether. Throughout the journey the MG Car Club people in Australia gave us great support.

Eventually we arrived in Sydney. This came as something of an anticlimax, especially as, when we had six hours driving still to do, we knew who had won the Rally. We were disappointed because we felt we could have done so much better as the engine of the MG was still going beautifully. Nevertheless we were the only sports car to finish — and we could have been unluckier and been put out altogether by the radiator.

The one big setback, towards the end of the run, has made us more determined to have a go in the next Marathon. We enjoyed every minute of this one, and we know the car can do it.