This article was written for the Petrolicious Drivers meeting at Bicester Heritage on Sunday May 12th 2019. The words and photography are by Andrew Coles Next Step Heritage .

MG Car Club – 1968 MG B

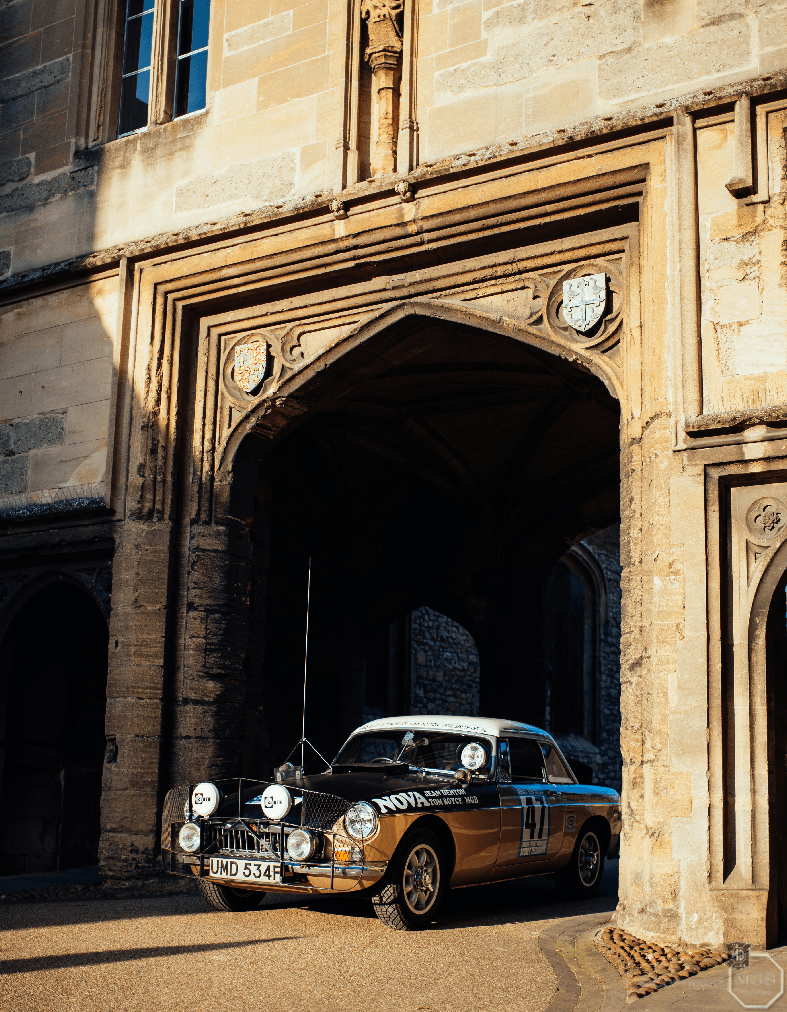

The long-lost London-Sydney MGB is discovered and restored by the club

instagram @mgcarclub

It was epic in the truest sense of the word, a cross- country race from London to Sydney. An old-school, hairy-chested, wild west adventure barrelling full-tilt into the unknown; an odyssey designed to captivate a nation and spread the good English word wherever it went. The first running of the London-Sydney Marathon would cover more than 10,000 miles in just 14 days on the road.

But this ‘boy’s own’ adventure wasn’t just for the boys. The glamorous Jean Denton – racing driver, marketer, first president of the British Womens’ Racing Drivers Club and future parliamentarian when she became Baroness Denton of Wakefield – along with her navigator Tom Boyce, took on the escapade of a lifetime driving this very MGB. Some 47 years later, as a rusting hulk, it fell into the lap of the MG Car Club, who crowdsourced its restoration to the exact state in which it departed London’s Crystal Palace that night in November 1968.

The Daily Express-Sydney Telegraph London-Sydney Marathon, to give it its full name, was the brainchild of Sir Max Aitken, World War Two fighter ace and son of Lord Beaverbrook, proprietor of the Daily Express. The pound was weak and confidence was low, so what better way to raise spirits and spread the message of British engineering superiority around the world than a cross-countries race? With the full force of the Aitken family publicity juggernaut behind it and a £17,000 prize pool waiting in Sydney’s Hyde Park, the London-Sydney Marathon filled the front pages of newspapers wherever it went.

The big works teams from Ford, British Leyland, Citroën, Holden and Rootes brought the might. They employed famous drivers such as Paddy Hopkirk, Rauno Aaltonen, Roger Clark and Ove Andersson and provided service crews who leap-frogged the rally in private planes, waiting in remote locations with spares, fuel and tyres. But the majority of the 98-car field, whittled down from a reputed 800 applicants, was comprised of amateurs and semi-pros who were hoping for nothing more than an adventure. The ultimate embodiment of this was surely the CKW Schellenberg team, who took part in a 1930 Bentley Sports Tourer.

We can only dream about the sparkle of anticipation and adventure in the eyes of Denton and Boyce as they departed from the now defunct Crystal Palace circuit in front of a reported 20,000 cheering fans and tens of thousands more who lined the streets all the way out of South London.

There was thick fog on much of the overnight route through France, and then ice was the main challenge as the rally made its way via Italy, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, across the Bosphorus to Istanbul. The event was scored on timed average speed on stages, which began in Turkey, although the schedule was so tight that competitors drove at near competition speeds on the open road to simply keep up.

Departing Istanbul, there was doubt as to what exactly the road ahead through Iran, Afghanistan, and through the Khyber Pass into Pakistan would bring. This was the height of the Cold War and the more remote parts of these countries were rarely visited, let alone by a ragtag assortment of racing drivers and their crews. After a sprint across India via Delhi and Agra, the first 72 crews to Bombay (now Mumbai) boarded the waiting P&O liner S.S Chusan, bound for Australia.

The Daily Express had worked its magic and the crews were treated as superstars everywhere they went. They arrived to a media frenzy at each scheduled stop and navigation often wasn’t required, especially in India. The crews just followed the crowds lining the route.

The nine-day ocean crossing provided some respite, but the rally restarted in earnest on arrival in Perth for the three-day, 4,000-mile sprint, on mostly unpaved roads across the Australian outback. It was on one of these tracks that Denton and Boyce suffered their closest call. After crashing into a hole in thick bull dust, the engine broke its mounts and slid forward into the radiator, damaging it irreparably. Thankfully, members of the MG Car Club Western Australia had been following their progress and had arranged a support network. They managed to repair the mounts, swapped a radiator out of a member’s similar car, and had the MGB on its way to Sydney. Denton and Boyce came in 42nd place of 56 cars that made the finish.

Little is known about the MGB’s history. Denton had previously raced it at least once at Mugello in Italy, but with backing from groundbreaking fashion publication Nova, which described itself as ‘a new kind of magazine for a new kind of woman’, it was repainted gold from the original British Racing Green for the London-Sydney Marathon.

After returning from Sydney Denton drove the MGB in the Scottish Rally, but from there it

disappeared into obscurity for more than four decades until an email landed in the MG Car Club’s inbox at Kimber House, their Abingdon headquarters, in April 2015.

The MG Car Club traces its roots to 1930, when the club was part of the Morris Garages company. Its headquarters are located next to the original Abingdon factory and Kimber House has become a famous destination for its 14,000 UK members and 55,000 international affiliates. Kimber House sits on the original run-in test drive route and can claim that every MG built from 1929 to 1980 drove right past its door.

That unsolicited email was from a rubbish removal contractor who had just cleared an old property. He had found a very rusty, purple MGB that didn’t run and he wanted £1000 for it, which is a considerable amount when the car appeared only fit for the scrap heap.

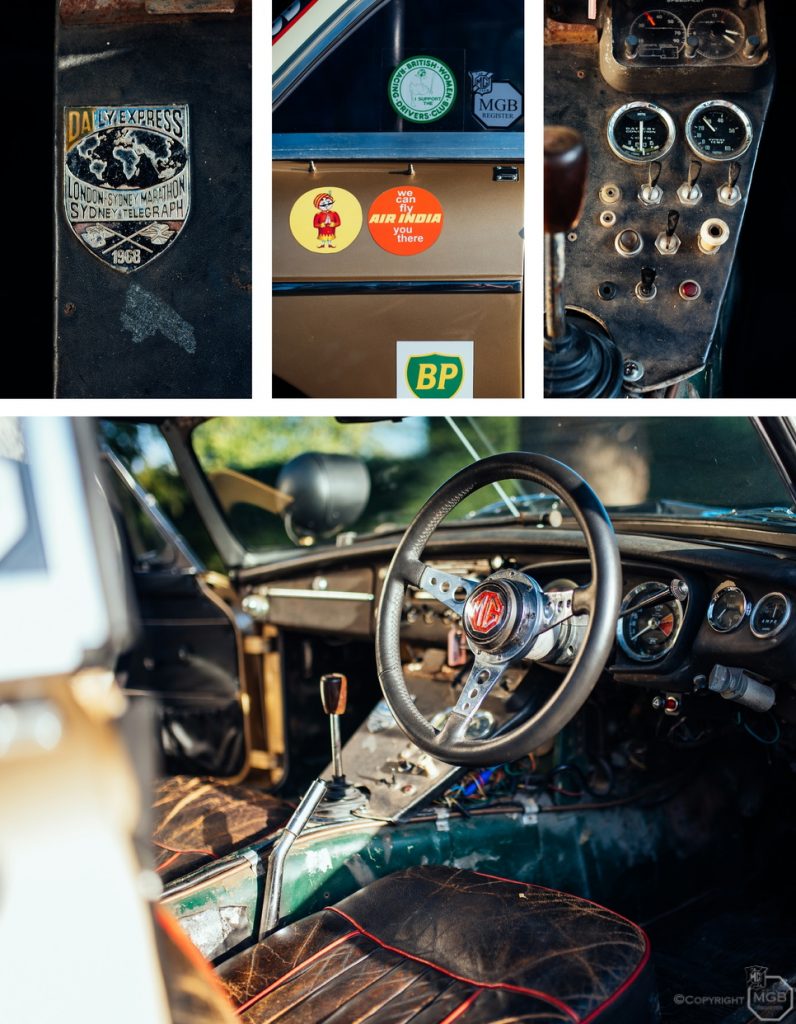

Clubs frequently get these kinds of emails, but there was something intriguing about this forlorn purple roadster. Club member Bill Price, ex-manager of Special Tuning, BMC’s in-house race preparation department, confirmed that the roll bar and spare wheel carrier were factory race parts. The club archivist had a hunch, and a check of the registration plate revealed that the long- lost London-Sydney MGB had indeed landed in their laps.

Inspection of the car revealed that special chassis reinforcements, 24-gallon long-range fuel tanks, the low-compression engine built to cope with poor quality fuel, and the bespoke telescopic rear damper setup engineered by Alex Moulton, co-collaborator of the original Mini with Alec Issigonis, all remained in place. The question of what to do with such an important car was raised and MGB Register chairman, John Watson, took charge.

‘The MGB Register acquired it, and we were inspired by the model used to restore the Vulcan Bomber, where people could donate to the project and have their name associated with it,’ says Watson. ‘We sought donations starting at £25 from members, companies like Moss and British Motor Heritage helped with parts, and Abingdon Car Restorations did the bodywork at a hugely discounted rate.’

While the bodywork of the car was in a sorry state, the interior remained as it was during the rally. The original British Racing Green colour can still be seen, the period correct Halda Speedpilot rally tripmeter is fitted, and amazingly, the original London-Sydney Marathon finishers medal remains stuck to the console. Only the reclining lay-flat passenger seat, designed by the London College of Physicians to allow sleeping on the move, was missing.

One club member supplied a set of Cibie rally spotlights, and another donated the genuine ex-works hardtop, identical to what the car used in 1968. The sign-writing was recreated from photographs, and the club used its close ties with MG’s current owner, SAIC, to recreate a missing Air India sticker.

‘None of the photos we had clearly showed the fine detail of the sticker,’ says Watson. ‘We were already working with MG on a heritage project ahead of their launch into India, so we asked their Indian marketing manager if she had any suggestions. Within 24 hours she came back with the artwork for every Air India logo of the 60s and 70s!’

Response to the car has been terrific, and the finished product is a great demonstration of the club’s capabilities. There are tremendous, and rarely tapped, reserves of knowledge and experience in many clubs and the freshly restored London-Sydney MGB is the physical manifestation of that.

Much as UMD 534F had inspired MG Car Club members across the globe in 1968, it continues to inspire them today, more than half a century later.

Words and Photography: Andrew Coles @agr_andrew